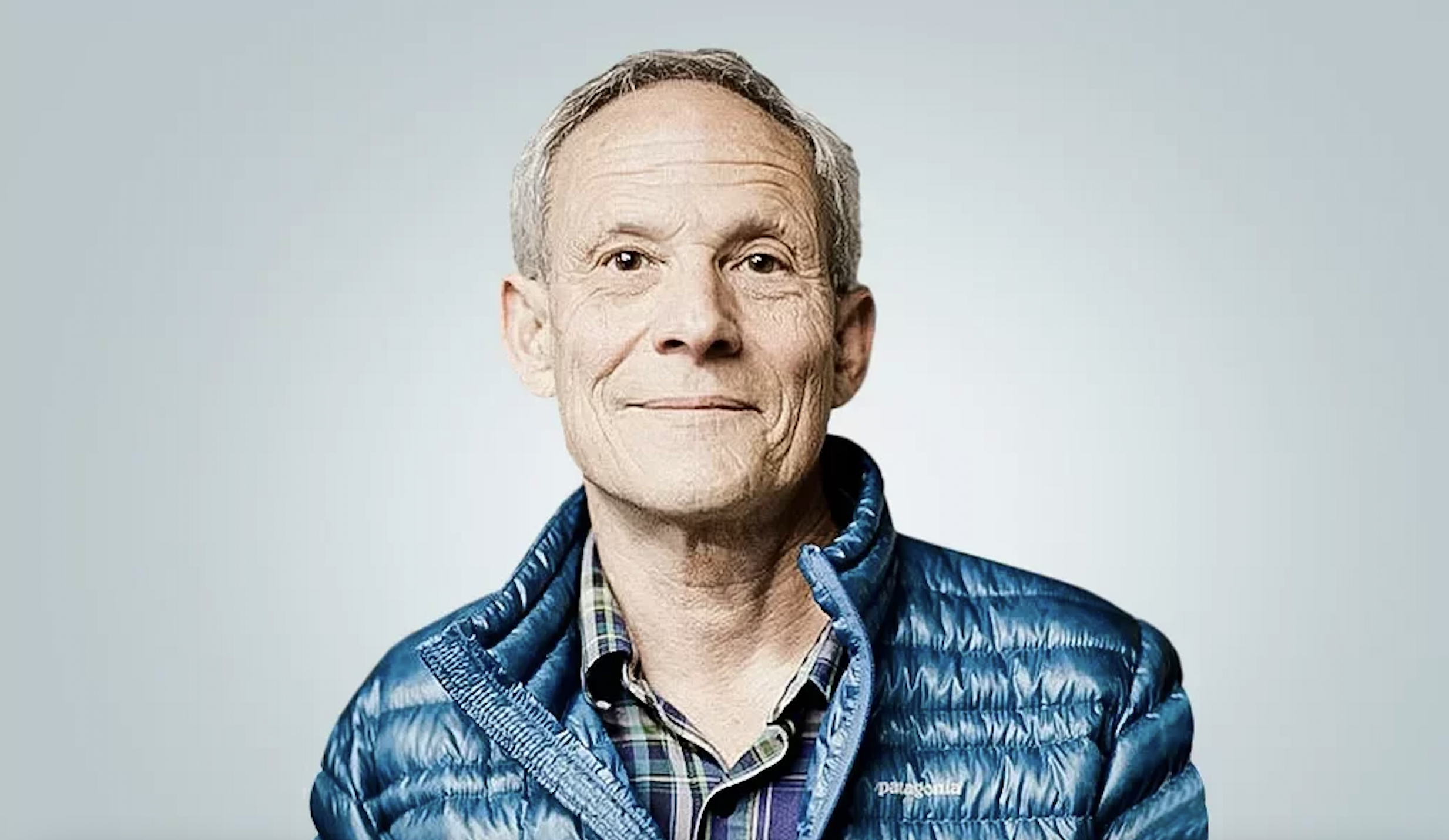

It’s an icon. A brand highly recognizable with its flashy color robust bags and its several commitments towards a sustainable future since the early days of 1973. Patagonia has served as an example for many years way beyond its industry and one of the early employees, Vincent Stanley, serving now as the Director of Philosophy, have been at the heart of the story, he knows everything inside out. Also poet and author, he eventually co-wrote The Responsible Company with Yvon Chouinard, the founder of Patagonia. We sat down with him for a conversation that you may also be able to watch it on video further down this article. This is the first episode of a series of conversation with change makers that will drive inspiration in what you do. For the better.

You’ve been in the company for decades and director of Philosophy for the last nine years. What have you learn during that period of time?

What we call the Patagonia philosophy go back to the late 1980’s early 1990’s and we have had several period of strong growth. In some extant, there were more challenging for our values than the other time, and during the 1980’s we were without direction. Sales were growing 40 to 50% a year but we were adding new lines like crazy. At one point, we had three sailing lines for different classes of boats, a line for horseback riding, people you’d meet on a plane were ready to come and join to work for the company on the next week. I think Yvon (Chouinard e.d.) at a certain point was asking: ‘Am I creating a company that I don’t want to own or work for every day?’ So he started to gather employees, about 30 at time, in some remote places like Yosemite, and sit outside in a circle. Talking about how we want to do business, what do we believe in. And he took people by function, so the finance people got together, sales, HR, etc. And we came up with this document that I put up together as an internal book in 1991. And that became heart of Let my People Go Surfing fifteen years letter when it got published. The thing that was interesting is the way we formulated these philosophies as a child growing rapidly but we finished at a time we were suffocating. Cause we overextended ourselves, we have borrowed too much money and after the Berlin wall fell, this industry collapsed in Los Angeles and we got in trouble with our bank. We finished writing our philosophies in 1991 when we laid off 20% of our employees, contracted quite a bit.

“Period of growth were more challenging to our values”

Yvon used to teach several classes in seminar style gather ten or twelve people and he got tired of it, he stopped. So when I retired from operational responsibilities I wanted to teach the classes but the environment was so much different than when Yvon was teaching them. Cause we had all these things written down for decades. It’s something I would advise any company that wants to live according to its values to be really careful about writing things because it really helps in the absence of individual discussions, our employees took to heart. So I what I did with the classes is something similar but not take people by function, I would have a child care provider and a salesman in the same room and have them talk about a value that they share but makes their work harder. This is the background, I worked about a third of the time with employees, one third of the time on graduate students -I had a relationship with Yale for ten years on the environment and business school- and then a third of the time with B-Corp. Business that wanted to cope with Patagonia, aiming at operating according to their values. So long answer to your question but I hope it answers it.

When you write such a piece, is it set in stone for ever or do you leave it grow?

I think it has to change but if you’re doing a good job, the changes will occur more slowly than you would expect. For instance, the design philosophy that we described in 1991 took form of nineteen question rather than “do this or do that” format. Is the product long lasting, is it durable…? One of the things we noticed 25 years after we wrote that is that we had nothing about reparability. And now that is very strong design value for us cause it really last the durability of the product. So everything has to be reexamined periodically but I think if you do a good job, the basic values will hold for a long time. We had a purpose statement that last for 27 years and then we finally decided this isn’t enough and we feel very differently, we wanted to simplify it. It went from ‘Build the best product causing no necessary arm and use business transparent implement solution to the environment crisis’ which was too complicated to: ‘we’re in business to save our home planet’. The first mission statement was something that everybody took it so much to heart, it was something that wasn’t quite true when we adopted it because we didn’t know enough about the supply chain to really reduce the arm we were doing. But it was something we embodied for 27 years. But there again, people asked “how does this affect my work with my team, how do we change to embody this?”

“Success permeates this culture of improving the social and environmental practices. And it works against despair.”

After that, did you have to adapt it into specific details?

Yes and, you know, the needs of 99% of the business are commons among companies. In a way, we have more in commons with Exxon in a way than with a non-profit. So what have been experimental for us is to continue to be strong as a business and yet really question everything we do in a business that creates some arm and to reduce that. I’m giving you an example: an employee was talking about her trade show booth and she said all of her counterpart from other companies were changing their booth every two years and they didn’t worry about it. Whatever the needs, the budget passes when she was able to keep it for ten years and everything had to be recycled according to our values. And whenever she had to change her booth, everything had to be recycled. So those constrains forced everyone to think and inspired other business model. So you can’t fall asleep saying ‘I don’t worry about this or that’.

You made knowledge a key factor to your success. There are so many companies that are claiming doing good but when you go deep, there’s not much to back it up. How did you organized at a company level to make sure that what you were standing for remained strongly backed by evidence?

I don’t think that question is ever settled. To give you an example, we set up a goal around 2017 as we wanted to become carbon neutral by 2025. But we realized that carbon neutrality is a very easy goal, all you do is to buy a lot of credits and then you’re home free. But then it doesn’t really reduce the emission, it doesn’t really help the environment, so we change that. We know 80% of our environmental impact is in materials so we’re going to commit to not use virginial oil in materials by 2025 and we got here this year (2023). But the emissions aren’t down enough. Because the real emissions come from the factories that makes the fabrics and still use coal as energy. So now is the question ‘how we work with the mills to help them to convert to renewable energies’. But there are much bigger than we are, they have many customers so if you’re actually really working on problems, not just trying to say you’re working on them, the problems getting in a way are even bigger. I think concentrating on the objectives and questioning those in terms of ‘are they enough’ kept us honest. We’re on pedestal so well regarded and trusted that we are well conscious about it that if we don’t live up to that we will be a big target. That’s also an influence.

“The design philosophy that we described in 1991 took form of nineteen question rather than “do this or do that” format.”

You have to take all the value chain to be influent and all the companies don’t necessarily want to have that level of commitment with their suppliers, so how do you cope with that burden in a way at a company level?

There are a couple of approaches to this question. What I mentioned about trade shows is nothing compared to other things we do so we have to constantly get hard information on what we do and what has been done in the supply chain. So a company that doesn’t want to know has no way to solve these problems. Because there are just invisible as there were to us until we took down that path. And you cannot sleep on them otherwise there’re coming back a hundred time stronger at you.

You still have to prioritize them…

That’s what I’m looking at: what type of major product we need to be looking at, what are our main environmental and social challenges. But on a day work, all of our people working for Patagonia are concerned by the big problems. And you want to make it possible for this people to as proactive as possible and support them.

You took an active role in B-Corp, Faire-Trade USA, Footprint and many others. It teaches us that you have to work in a systemic way because there is no way you can do all of this on your own. When did you realize that and putted into motion?

The education for us was more in labor than on the environmental side. Cause, again, as a global company primarily if we have clothes made in factories and those factories are making clothes for other brands, it’s the same labor condition applied to us. On US law you can’t collaborate with other brands, but you can work with an NGO that we helped start the label to look at it. In early 1990’s we started to look at cooperation and we also have worked on certification for materials, shared practices for animal welfare. And we’ve established these standards that are even difficult for us to meet so we haven’t had a lot of people to claim on, but it raises the standard that other people use.

When you set these standards, these priorities, are you referring back to the core of your philosophy or is it so integrated now that you don’t have to go look at it?

It’s more attached now to what everybody’s doing. Sometime, people will go back to core philosophy or to Let my People go Surfing to find a way to act upon what they do but for the most part it’s ingrained in what people do. To give you an example, when we grew our warehouse, we only had one in the US and we knew we needed one on the East Coast so our finance and operation people were driving around with real estate agent that was showing them refineries to put a 30.000 square meter warehouse. And they got together at the end of the day saying ‘we can’t do that. This is not keeping with what we do’. So even if the environmental side of the company was not telling them to do that. Then we located the site on a reclaim coal mine that have been damaged in a mining accident sixty years ago.

“We’re on pedestal so well regarded and trusted that we are well conscious about it that if we don’t live up to that we will be a big target.”

What are you the proudest of during this span with Patagonia and the breaks you took from it?

I ended up working with a non-profit in Maine to take out a dam that blocked seventeen miles of ground for all of these fish to access the ocean and the dam was only providing 1% of electricity for a small city if 40.000 people. The owner of the land didn’t want to give up the tax break he had so I got together at six o’clock every morning on the phone with the people who worked on it and I wrote several full-page ad that the New York Times and the Washington Post published. We’ve had the first dam removed against the wish of its owner. The fish have come back, the birds came back to the river so I’m very proud of that.

You should! Last question now: giving the state of the environment today and the trajectories the scientists are giving ug, how do you stay -if not positive- at least energized enough to tackle this topic?

One of the things that’s helpful is that we build up a culture of various successes. We’ve been able to change practices we couldn’t have thought we could and that builds a level of confidence for an organization as well as it does for a person. It’s almost like an athlete that would say ‘ok I can run this fast, I want to beat my time next time’. That permeates this culture of improving the social and environmental practices. And it works against despair. Some people are optimists, some are pessimists, but everybody has a sense of urgency that there’s something that they can do. And they’re able to support their families doing that so it’s not a level of ‘I’d love to do that but I won’t be able to eat’. People feel they have a community, a support and that they can bring their values to work every morning.

Photo credit: Vincent Stanley

Watch the full video of the conversation with Vincent Stanley: